Transforming the NYC Street - Part 1

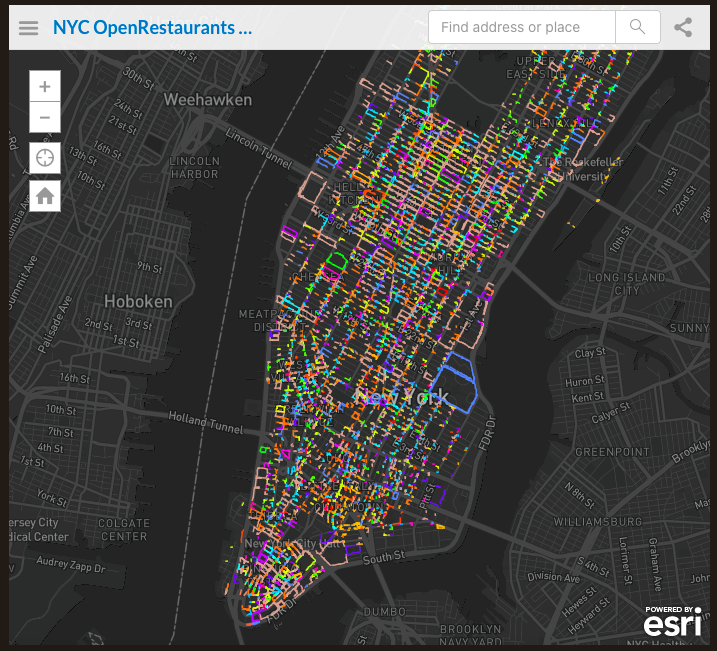

A Map of How NYC Department of Transportation is Changing the Big Apple's Streetscape

Originally published in Vivacity’s Blog.

This is a multi part series where I will be discussing the impact that Open Restaurants has had on New York City and how it should lead city planning, architects and owners to fundamentally rethink streetscapes and zoning.

On this first blog, I want to describe what led me to build a comprehensive map that catalogs the available curbs to be used as Open Restaurants.

If you want to skip my long explanation, you can simply click here and explore the map.

Part 1.1: A Map of Open Restaurants.

Covid-19 has changed cities for better or for worse.

In New York City, the change can be imposing. The other day I biked from Inwood all the way down to Greenwich Village and was shocked by the amount of solitude I witnessed. In early September, there were barely any cars, which was great for my cycling experience. In the small streets that make the Village feel like a village, I saw a couple of restaurants set up their outdoors Open Restaurant pavilions. Their presence was hard to miss, they have fundamentally changed street landscapes in New York City. I was happy to see that other neighborhoods other than Inwood are experimenting with how to fundamentally transform their streets. Kudos to NYC Department of Transportation for being proactive and collaborating with restaurant owners to reclaim streets for pedestrians. For those of you that do not know, while NYC has always allowed restaurants to deliver their food, it was only a couple of months ago that the city allowed restaurant owners to serve and host their customers, but only if they sat in outdoor pavilions built to specifications.

Since the city allowed for restaurants to accept sitting customers, many restaurants have taken the initiatives to build their pavilions; transforming many streets from being full of parked cars to pedestrian friendly, sit-down dining areas. I have seen this first hand in my neighborhood near Dyckman Street.

After observing them for weeks, I have come to fall in love with them. Restaurants are innovating in this mini urban architecture. Sidewalks and streets now feel relatively safer. Most people who choose to dine out are wearing their masks and practicing, to an extent, social distancing. I have noticed that pedestrian activity along the part of the pavilion that faces traffic has generally increased, and cars slow down when drivers are walking to board their parked vehicles. There are also nooks and crannies that sometimes happen between parking spaces and the pavilions that allow for rental Revel motorcycles to park or for a delivery person to be able to park their e-bike.

Sometimes there is a secondary or tertiary activity around these pavilions. I have seen domino tournaments coexist with people eating fancy mofongo. I have also witnessed people selling home made Gucci designer masks next to the small vendor with the make-shift piragüa stand selling empanadas a couple of feet away from a restaurant pavilion on Nagle St.

All of the new social and commercial interactions on the streets got me thinking about the potential activity around them. So I decided to map where these curbs could legally exist.

Part 1.2: How I Build the Map.

Naturally, the first place I went in order to create a map of NYC Open Restaurants Curbs was NYC Open Data. After spending an afternoon navigating the datasets they had, I decided there was enough data to get to a map that could have curbs categorized by restaurant. I set myself a road map that was roughly as follows:

Get the data from NYC Open Data

Clean the data

Run a typology analysis

Write rules to determine how curbs and streets relate to one another

Enhance and post-process any data after applying the rules.

Publish a web map

The data sets that I found helpful in the NYC Open Data portal were: the parcel layers, the street centerlines, the curbs, the sidewalk polygons, and the building footprints. At the time I did the analysis, the Open Restaurants applications and inspection layers were not available, so I used the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) New York City Restaurant Inspection Results data set to establish what buildings and parcels had an operating restaurant. I created a view with a unique CAMIS, which is the unique identifier DOHMH uses to identify restaurants, along with the unique Building Identifier Number (BIN) and the unique Parcel identifier (BBL). This data set, according to the providers only captures active restaurants, but given how the pandemic has decimated the restaurant industry, it might not capture the micro-closures of the past months. So this method might over calculate the number of available curbs for Open Restaurants. Nevertheless, this approach allows to capture the total capacity the city has to implement Open Restaurants, as it does not limit itself to either restaurants that have applied to the Open Restaurant program or to curbs the city has officially designated as places where sidewalk cafes can be constructed. In either case, the dataset needs to account for the reality that some owners might choose to build unapproved or ilegal pavilions (some restaurants, for whatever reason, might choose to implement open restaurants without self-reporting to the program).

After I downloaded all the datasets, I proceeded to clean the data on my desktop using ArcGIS Pro, making sure that the schema of the datasets match for the pipeline of spatial and table operations I was about to perform.

The first thing I did was to join the DOHMH Restaurant Inspection table to the building footprints and the parcels. I was not sure which of the two layers I would end up using given that the final results would vary from the initial shape. After double checking that the buildings dataset joined to the CAMIS number using the BIN number and that the parcels dataset joined to the CAMIS table using the BBL number, I was ready to strip the new layers of any unnecessary tabular information that would make doing data analysis slow or that would affect the performance of the layer once I published them to the web.

I also wanted to keep the scope of the project under control, so I decided to do the analysis only for Manhattan. This would allow me to set up a streamlined pipeline without worrying about having to deal with data problems from five boroughs.

Now with the data filtered for Manhattan only, I had the two layers ready to manipulate. The curbs that come from NYC Open Data are drawn by block and they are not split nor categorized. They do not have a BBL or a BIN associated with them. In order to determine what part of the curb belonged to a building or a parcel I had to come up with a way to split the curb by the length of the parcel or building. But in order to determine how to split the curb, I needed to determine what was the front of a building or a parcel. This sounds like an easy thing to say — in our heads we point and say: “look, that's the front”. But geospatially, it is a hard thing to determine. I remember attending an APA conference a couple of years ago where Pascal Mueller, the Director of Esri’s R&D at Zurich,was explaining how hard it was to determine what a building front is to a conference room packed with planners. In reality, parcels and buildings have a front in relation to the street and one another, not to the curb. To determine the front of a parcel or a building, I needed to establish a relationship between any of these two layer to the street centerline. Since my plan is to eventually build 3D models from these curbs, I decided to use City Engine. City Engine has a tool that allows polygons to establish a topological relationship to the street and helps determine the front, back and side parts of a parcel. I had a second reason to start using City Engine, and that is that further down the line, I knew I wanted to transform the NYC DOT rules for Open Restaurants into 3D procedural rules. So, I established a pipeline between my ArcGIS Pro Environment and CityEngine in order for me to quickly experiment and see results and be able to get to the final product: a map of categorized curbs. After topologically establishing the front of buildings and parcels, I decided to use the parcel layer instead of the building layer because some parts of the buildings were indented back or had weird corners that made it difficult to recognize them as fronts. The parcels aligned better perpendicularly to the curbs that I plan to split. Using City Engine, I wrote a rule that categorized each parcel according to the street relationship and then used the offset operation to parametrically offset the front line of the parcel towards the street. This created a flat 3D multipatch that overlapped with the unbroken curbs. I exported these multipatches to a geodatabase and imported them back into ArcGIS Pro to further manipulate the curbs using Pro’s analytical tools. Once I had the multipatch in ArcGIS Pro, I converted them back into polygons using the Building Footprint tool. Since these multipatches inherited the parcel’s BBL, I could associate the curb back to the parcel it originally belonged to. Then I used the Intersect tool to split the curb lines with the output polygon I generated using the Building Footprint tool. Now that the curbs were split, I could associate each curb back to the parcel and join the CAMIS data along with the type of cuisine attributes. The Intersect gives me curbs that are close to the final product. The last step is to consider the Open Restaurants proximity rules with fire hydrants. I once again went back to NYC Open Data and downloaded NYC’s fire hydrants dataset. The Open Restaurants guidelines require that all pavilions constructed should not overlap with a fire hydrant within 15 feet of the hydrant. A quick buffer with a radius of 15 feet gives you the radius that can be used to determine what part of the curb is inside the buffer. I used the Erase tool to eliminate this part of the curb since it cannot be used for Open Restaurants pavilions. Finally, the Intersect and Erase tools left some lines that were quite small. I calculated the curb length and queried and deleted any fragments that were smaller than 10 linear feet since I thought that 10 feet is the minimum dimension required to be able to build the walls and accommodate the seating configuration that Open Restaurants requires.

And there you have it. That is how I built this categorized map of all curbs in Manhattan.

I have two notes about this map and the new dataset. First, there could be other methods to produce a more accurate map of curbs. The method I used is not the best way to map restaurants in NYC because there are restaurants that coexist on the street level of a building. Furthermore, some parcels may also have multiple buildings which are subdivided at the ground level to accommodate multiple restaurants and food vendors. I could not find a detailed enough GIS layer that had all these establishments mapped per building as individual polygons, so there is a high probability that I missed restaurants that coexist at the ground level of a building. Even if I had decided to do this process using the building footprints instead of the parcels, I would have run into this problem. There is a way to calculate the margin of error and find out what restaurants were dropped using this method. One could then subdivide the curb using proportional distribution by making some assumptions, like inferring a certain frontage in relation to the business square footage. My second note has to do with an attitude towards what the end goal is. I believe there are clear rules that NYC DOT has adopted towards implementing these pavilions, but these are being done without much oversight when it comes to approval. Looking at the curb as part of the parcel instead of the building frontage seems to align more with how these pavilions are going to most likely be built. NYC DOT, NYC DOHMH, and City Planning will probably end up negotiating with the restaurant owner the design and terms of how the pavilion continues existing after it has been built, as long as it does not conflict with public safety or traffic issues.

In any case, the solution and pipeline I built to create the curb map could be modified with better and more accurate data to further refine how curbs are being categorized, and how they are being used to monitor and inspect the pavilions. One last thing: like I said above, I decided to do this only for Manhattan, but the pipeline remains the same if there was a need to do this in any other borough. The pipeline is scalable as long as the data to produce the curbs exists. And for New York City the data exists.

A static view of curbs categorized by cuisine.

A static view of the Open Restaurant dataset on a web map.

Part 1.3: Some Analysis Extracted from the Data and Map.

And now for some fun stuff!

I decided to run some analysis once I created the categorized curbs. When I do spatial analysis, I like to think of the question first, and then see how the data answers the question. So without further ado, here are the questions I asked my dataset.

How many linear miles are available to implement OpenRestaurants in Manhattan?

662 Miles of linear feet are available for Open Restaurants in Manhattan

A static map of curb length per restaurant. Distance is in miles.

What type of cuisine has the most available linear street curb in Manhattan?

Restaurants categorized by DOHMH as “American” have the most street curb, followed by Cafes and Tea Houses, restaurants categorized as “Others”, followed by Italian, Chinese and then Pizza. I am a little bit surprised that Pizza was not number one on the list of linear miles, but then again, pizza shops in NYC tend to be small and have narrow frontage.

A static map showing the most frequent restaurants per curb (top 5) per cuisine.

What type of cuisine has the least linear feet in Manhattan?

Cuisine categorized as Iranian, Creole, Basque, Indonesian, and Scandinavian.

A static map showing the least frequent restaurants per curb (least 5) per cuisine.

What type of cuisine faces wide streets the most in Manhattan? What type of cuisine faces narrow streets the most in Manhattan?

A static map showing top 10 cuisines facing a narrow street. (c) Vivacity 2020

Top 10 cuisines that face Narrow Streets in Manhattan

A static map showing top 10 cuisines facing a narrow street. (c) Vivacity 2020

American

Cafe, Tea house

Other

Italian

Chinese

Japanese

French

Pizza

Mexican

Bakery

Top 10 cuisines that face Wide Streets in Manhattan

A static map showing top 10 cuisines facing a wide street.

American

Cafe, Tea house

Other

Chinese

Pizza

Italian

Mexican

Japanese

Latin

Bakery

What parts of Manhattan have the highest capacity for Open Restaurants?

The Downtown/Wall Street and Midtown areas have the highest amount of available curbs to support multiple cuisines. This makes sense given that most food services revolve around the Financial District and the office clusters in Midtown.

A static map showing density of curbs per neighborhood. (c) Vivacity

My favorite analysis was the breakdown of cuisine facing narrow and wide streets. I liked this analysis because one can envision a future were NYC's DOT and City Planning allow cultural identity to project itself to the streets. I am imagining a future where NYC becomes more relaxed about regulating streetscapes and cars, and pedestrian traffic gives way to the street environments depicted in Netflix's Street Food in Asia and Latin America. Perhaps having chefs cook outside on the streets and having more people eat outdoors could help activate neighborhoods that now seem dormant. The analysis made me think actively of how street planning and programs like the Open Restaurants are helping maintaining the cultural diversity of neighborhoods like Washington Heights. The street level plays a crucial role in transforming neighborhoods to be more local and more humane in a city that is already tormented by having to practice social distance for an unknown period of time.

So what do you think? Do you have any questions you think I should ask the data set? Is there a specific spatial analysis you would like to see with this data?

Conclusion:

I built this map because I saw a need to understand spatially what I was witnessing at a local level in my neighborhood. The data was not immediately available, so I had to combine datasets and perform basic spatial and topological analysis to determine how curbs relate to building and parcel fronts. The final product shows curbs split by parcels, categorized using the CAMIS system. This data could be useful for the NYC DOT to maintain a digitized twin of curbs that could be transformed into a sitting area. This data set could also be useful for the NYC Department of City Planning to see how new regulations from NYC DOT might affect the land use and zoning for mixed used and commercial buildings at the street level.

I have made the dataset available free of use. You can find the repo with the data here.

I made this analysis weeks before the DOT uploaded their Open Restaurant Applications and Inspections data set. Perhaps in the near future, together with our new curb data set, we could perform an analysis of these new datasets and include them into our NYC Property Portal system.

Up Next

In my next installment, I will be using the curb data set as the starting point to procedurally create the Open Restaurant pavilions in 3D using the NYC DOT rules. Sign up to our newsletter to receive updates on our blog postings.